The jazz world lost one of its most thoughtful voices when John Abercrombie, the guitarist whose delicate touch and harmonic daring reshaped modern jazz, passed away on August 22, 2017, at a hospital outside Peekskill, New York. He was 72. The cause was a prolonged illness, though details remain private. Abercrombie didn’t just play guitar—he redefined what it could say. His sound, at once lyrical and adventurous, connected the warm, swinging phrasing of Wes Montgomery to the electric explorations of John Scofield and Pat Metheny. And for over five decades, he did it without ever shouting.

A Humble Start with a $40 Guitar

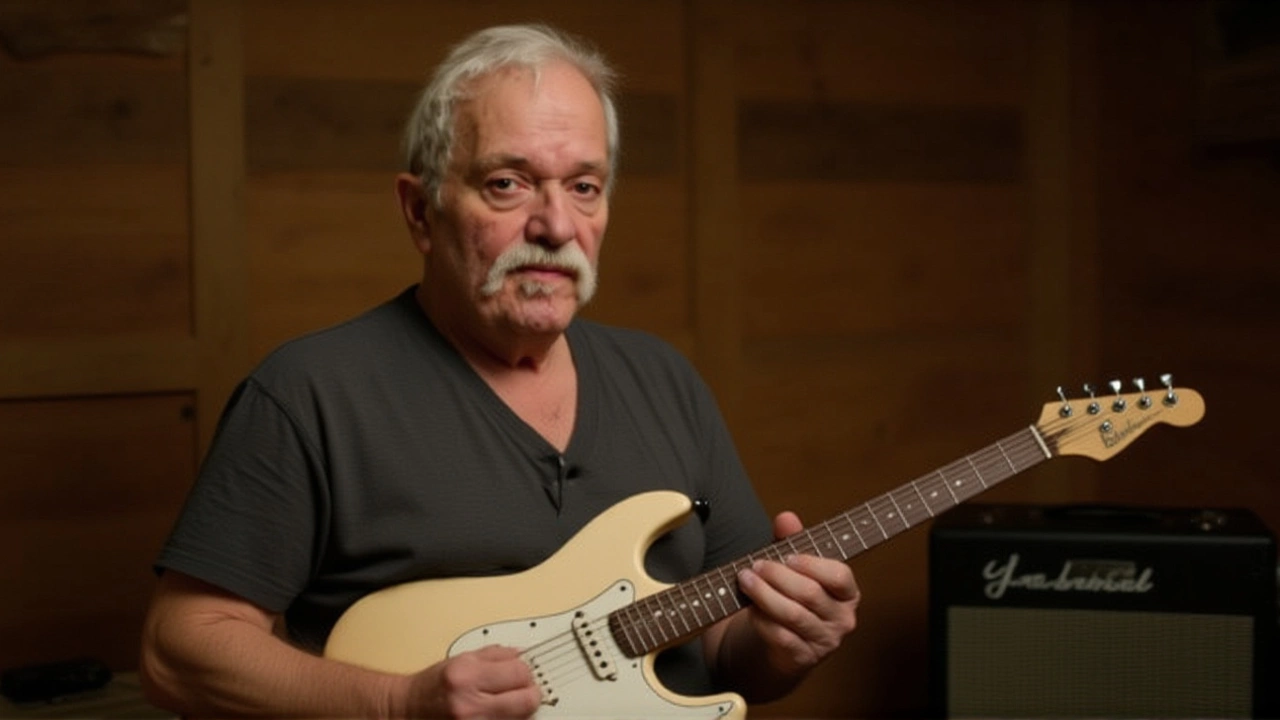

Born December 16, 1944, in Port Chester, New York, Abercrombie grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut, where he first picked up a $40 Harmony guitar. He later joked he used it as a baseball bat. His early heroes were Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley—but everything changed when a local teacher slipped him a Barney Kessel record. "That’s when I realized the guitar could whisper," he once said. By 14, he was copying Kessel’s bluesy lines. Then came Mickey Baker’s duo with Silvia, and suddenly, jazz wasn’t just music—it was a language he needed to speak.Berklee, Bands, and the Birth of a Sound

At Berklee College of Music, where he studied from 1962 to 1966, Abercrombie didn’t just learn theory—he absorbed history. He’d sneak into the Jazz Workshop after class to watch John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk live. He didn’t want to teach—"I was too young," he said. "I wanted to play." So when organist Johnny 'Hammond' Smith offered him a gig touring seven nights a week, he took it. His first recording, 1968’s The Soulful Blues, featured saxophonist Houston Person and drummer Grady Tate. He also played R&B on military bases with the Danny White Orchestra, learning how to groove hard.The Fusion Years and the ECM Breakthrough

By the late ’60s, Abercrombie was in the thick of jazz-rock’s rise. He joined Dreams, the horn-heavy band featuring Michael Brecker and Randy Brecker, then played on Billy Cobham’s 1973 album Spectrum, stealing the spotlight on "Crosswind." But the real turning point came when he met Jack DeJohnette. "We played everything," Abercrombie recalled. "Swing, space-rock, standards—it was the first time I felt completely free." That connection led to his debut as a leader: 1974’s Timeless, produced by Manfred Eicher for ECM Records.Forty Years with ECM: A Quiet Revolution

Abercrombie’s association with ECM Records became legendary. Over 30 albums as a leader, 20 as a sideman. He didn’t chase trends. He built worlds. His 1975 trio with DeJohnette and bassist Dave Holland—Gateway—became a touchstone for atmospheric jazz. Later, with Peter Erskine and Marc Johnson, he refined his sound into something intimate, spacious, and deeply emotional. His influences? A who’s who of guitar: Jim Hall ("the greatest impact"), Wes Montgomery, George Benson, Pat Martino. But he also admired the wilder sounds of Gábor Szabó, Larry Coryell, and John McLaughlin. "I was influenced by every guitar player who ever played," he admitted. He didn’t see himself as a revolutionary—he saw himself as a bridge.

Final Duets and Lasting Echoes

In the 2000s, Abercrombie formed a magical partnership with Ralph Towner, blending acoustic textures in ways few dared. His 1993 album Solar with John Scofield and 2007’s Coincidence with Joe Beck showed his ability to adapt, listen, and elevate. He recorded with saxophonist Jan Garbarek and bassist Eddie Gomez, always bringing quiet intensity to every note. His final album, Up and Coming, dropped in early 2017—just months before his death. It was subtle, reflective, and utterly beautiful. No grand finale. Just a man saying goodbye with his instrument.Why He Matters

Abercrombie never sought fame. He didn’t headline festivals or appear on late-night TV. But every guitarist who plays with space, with silence, with emotional restraint—every player who lets a single note hang in the air like mist—owes him something. He proved you didn’t need speed or distortion to be radical. Just honesty. Depth. A willingness to be vulnerable. His legacy isn’t just in his recordings. It’s in the students who heard his solos and thought, "I can do that too." It’s in the way Bill Frisell and Kevin Eubanks cite him as a quiet godfather. It’s in the ECM catalog, where his sound still echoes decades later.Frequently Asked Questions

What made John Abercrombie’s guitar style unique?

Abercrombie blended the harmonic sophistication of Jim Hall and Wes Montgomery with the atmospheric textures of ECM’s signature sound. He favored clean tones, sparse phrasing, and emotional restraint over technical flash. His use of silence and space—letting notes breathe—created a meditative quality that influenced generations of jazz guitarists, from Pat Metheny to Kurt Rosenwinkel.

How did ECM Records shape his career?

Manfred Eicher’s ECM Records gave Abercrombie artistic freedom few labels offered. The label’s pristine, reverb-rich production style matched his introspective playing. Over 50 albums recorded for ECM allowed him to explore trio formats, duets, and ambient jazz without commercial pressure, making him one of the label’s most consistent and revered artists.

Who were his most important musical collaborators?

His most defining partnerships were with drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Dave Holland in the Gateway trio, and guitarist Ralph Towner in their acclaimed duets. He also had significant work with John Scofield, Michael Brecker, Jan Garbarek, and Joe Beck. Each collaboration revealed a different facet of his musical personality.

Did John Abercrombie ever teach music?

No. Though he attended Berklee College of Music, he declined teaching opportunities to avoid the Vietnam War draft and because he felt too young to instruct others. He believed learning came from playing, not lecturing. His only formal teaching was through his recordings, which became essential study material for aspiring guitarists worldwide.

What was his final album, and how does it reflect his legacy?

His final album, Up and Coming (2017), featured a quartet with bassist Drew Gress, drummer Joey Baron, and keyboardist Marc Copland. It was understated, melodic, and deeply reflective—full of unresolved harmonies and gentle dynamics. Critics called it a quiet masterpiece. It didn’t announce his passing; it simply offered a final, tender conversation with his instrument.

How is John Abercrombie remembered by today’s jazz guitarists?

Modern players like Kevin Eubanks, Ben Monder, and Sheryl Bailey describe him as a quiet giant who prioritized emotional truth over virtuosity. His recordings are required listening in jazz programs from New York to Tokyo. He didn’t just influence technique—he taught musicians how to listen, how to wait, and how to say more with less.